|

|

Looking out the window (ra-file, 663 kb) |

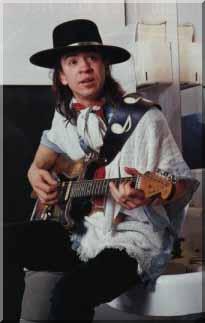

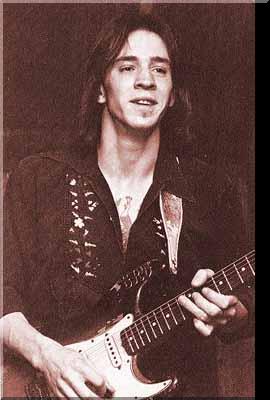

He was, perhaps, the greatest blues guitarist of his generation.Stevie Ray Vaughan, who died just 36 days short of his 36th birthday, played with

blistering, note-bending intensity, a gut-wrenching vibrato and tons of soul. His all-too

abbreviated legacy-five albums as a leader and a number of powerful sideman stints -

ended with a longoverdue collaboration with older brother Jimmie Lee Vaughan, on the

posthumously released Family Style. A well-balanced mixture of driving rock and

roll, smooth r&b, earthy funk and heartfelt blues, the album took SRV full circle,

back to his South Dallas days, paying tribute to the music the Vaughan boys listened to

and loved in the Sixties and Seventies. |

|

|

|

|

Writer Brad Buchholz recalled that magical night at Antone's in his Dallas Morning

News tribute to SRV: "The skinny kid in hip-hugger bell-bottoms and downcast eyes

blew away gruff old Albert King that night. At one point, Mr. King stepped away from

Little Stevie and hid his guitar behind the stage curtains, as if to say, 'This little

kid is scaring my guitar." |

By 1973 Stevie had traded his '63 maple neck Strat for a '59 rosewood fingerboard

model, which remained his number one guitar for the rest of his career. (In a bizarrely

portentous accident, the neck of his beloved '59 was snapped in two pieces on July 9 of

this year, when a huge piece of scenery at the Garden State Arts Center in New Jersey

crashed onto a number of SRV's guitars.) Little Stevie left the Nightcrawlers at the end

of 1974, and became the second guitarist, along side Denny Freeman, with The Cobras. |

| "I was sitting in the audience at a little club downtown on Congress Avenue

called After Hours," recalls Austin guitarist Van Wilks. "I was checking out

Stevie with The Cobras. Then, all of a sudden, Stevie starts singing that Freddie King

song, 'Goin' Down,' and I nearly fell off my chair. Everybody knew he was a great guitar

player, but nobody had ever heard him sing before. Later, he developed his voice into a

phenomenal instrument, even though he remained kind of shy about it. Hendrix said he

didn't like his own voice, either, and I always felt he had an incredible singing voice.

I thought the same thing about Stevie. I mean, there was more to him than just playing

single notes on the guitar." |

Word of Austin's hometown hero eventually reached the great r&b producer Jerry

Wexler, who flew to Texas in 1982 to catch Stevie Ray on his home turf. Considerably

impressed with the guitarist's talents, Wexler used his influence to place Double Trouble

on the bill at the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland - a coup almost unheard of

for an unsigned act. Stevie Ray's stinging Strat licks were well-received by his European

audience. Particularly impressed by the Texan's fiery fretboard work was David Bowie.

After Double Trouble's set, Bowie met with Stevie Ray to raise the possibility of the

guitarist appearing on his next album. Bowie eventually hired Stevie Ray to play on

Let's Dance and appear on his 1983 world tour. |

It wasn't long before opportunity came knocking once more on Stevie Ray's door.

Jackson Browne, a fan since his own encounter with Vaughan at the '82 Montreux Festival,

offered him the use of his Down Town studio, to record a demo that hopefully would land

Double Trouble a record contract. The taped results of Double Trouble's labors in

Browne's studio made their way to John Hammend Sr., the legendary talent scout and

producer, who counted Charlie Christian, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin and Bruce Springsteen

among his many discoveries. Excited by Stevie Ray's fresh take on an old formula, Hammond

purchased the demo and used his industry clout to secure a deal for Double Trouble with

Epic. |

While he was true to himself, he at the same time never failed to give credit

where it was due. In a 1988 interview, he noted: |

In some ways, he truly was that heir. "It just seemed like Hendrix was always

in his thoughts," said Austin guitarist Van Wilks. "He was certainly in his

heart and fingers. I remember one time we were talking about Hendrix - which is where our

conversations would always ultimately lead - and I pulled this Picture of Jimi's

tombstone from my wallet, which I'd taken when I was playing a gig in Seattle. I found

out that Jimi was buried in Renton, Washington, so I went there to pay my respects.

Anyway, when I showed Stevie Ray this picture, his eyes just got so wide - he couldn't

believe it. He just stood there and held that picture in his hand, and stared at it for a

long time." |

He returned to the United States a few days later. On October 17 he entered a

deter center in Marietta, Georgia, where he remained through November. Upon his release,

he returned to Dallas in an effort to escape the drugs, alcohol and late-night hanging

out that plagued him in Austin. |

© 1997-2008 www.corax.com - All rights reserved

Click here to help corax.com survive!

Stevie's first electric guitar - a gift from Jimmie - was a hollow-body

Gibson Messenger. From there he graduated to a '52 Fender Broadcaster another

hand-me-down from his older brother. By then, SRV had purchased his first record, a copy

of Lonnie Mack's instrumental hit. "Wham," which, alone with several Albert

King records, were the prime sources from which Stevie Ray shaped his own approach to the

instrument.

Stevie's first electric guitar - a gift from Jimmie - was a hollow-body

Gibson Messenger. From there he graduated to a '52 Fender Broadcaster another

hand-me-down from his older brother. By then, SRV had purchased his first record, a copy

of Lonnie Mack's instrumental hit. "Wham," which, alone with several Albert

King records, were the prime sources from which Stevie Ray shaped his own approach to the

instrument.  Jimmie played those "blues and originals"

in Storm, a gutsy trio that included future T-Birds bassist Keith Ferguson, and was soon

renowned in Austin for his guitar playing and comprehensive knowledge of blues and

r&b. Stevie dropped out of school and joined the exodus to Austin in the spring of

1972. Some time later he fell in with Crackerjack, which featured Johnny Winter's rhythm

section-drummer Uncle John Turner and bassist Tommy Shannon. That summer also marked the

first time he saw Albert King - who was to become his single biggest influence - perform

live.

Jimmie played those "blues and originals"

in Storm, a gutsy trio that included future T-Birds bassist Keith Ferguson, and was soon

renowned in Austin for his guitar playing and comprehensive knowledge of blues and

r&b. Stevie dropped out of school and joined the exodus to Austin in the spring of

1972. Some time later he fell in with Crackerjack, which featured Johnny Winter's rhythm

section-drummer Uncle John Turner and bassist Tommy Shannon. That summer also marked the

first time he saw Albert King - who was to become his single biggest influence - perform

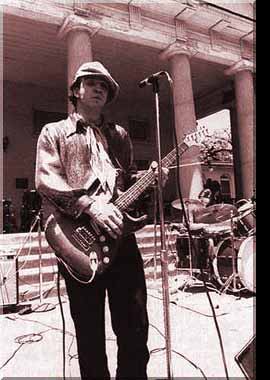

live.  By the summer of 1977 Stevie had left The Cobras to form Triple

Threat Revue, a versatile outfit featuring Mike Kendrid (composer of "Cold

Shot") on piano, W.C. Clark on vocals and bass, Dallas drummer Freddie Pharaoh and

the fiery Fort Worth vocalist Lou Ann Barton, who left the T-Birds to join Stevie's new

band. What with Stevie's Hendrix covers, Lou Ann's torch ballads and Janis Joplin covers,

and W. C.'s Freddie King covers, the band was indeed a Triple Threat. Ultimately,

however, egos clashed. As the Austin American Statesman's blues maven Michael Point put

it, "Lou Ann... really wanted a guy to back her up on guitar, and not show her up

with guitar hero tricks. And Stevie wanted a backup vocalist, not a star. That tension

was often visible on stage."

By the summer of 1977 Stevie had left The Cobras to form Triple

Threat Revue, a versatile outfit featuring Mike Kendrid (composer of "Cold

Shot") on piano, W.C. Clark on vocals and bass, Dallas drummer Freddie Pharaoh and

the fiery Fort Worth vocalist Lou Ann Barton, who left the T-Birds to join Stevie's new

band. What with Stevie's Hendrix covers, Lou Ann's torch ballads and Janis Joplin covers,

and W. C.'s Freddie King covers, the band was indeed a Triple Threat. Ultimately,

however, egos clashed. As the Austin American Statesman's blues maven Michael Point put

it, "Lou Ann... really wanted a guy to back her up on guitar, and not show her up

with guitar hero tricks. And Stevie wanted a backup vocalist, not a star. That tension

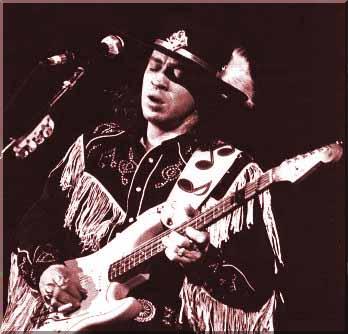

was often visible on stage." In 1984 Couldn't Stand The Weather was released, along

with a video - Stevie Ray's first - made for the title cut. The typically Texas-macho

clip received moderate airplay on MTV. This wider exposure helped push the album to

platinum and further cemented Stevie Ray's status as the reigning Texas Guitar King. As

he continued to forge his own identity on slightly-behind-the-beat Texas shuffles like

"Cold Shot" and "Honey Bee," he simultaneously pursued the ghost of

Jimi Hendrix, much to the delight of his young fans. If the connection was not apparent

from his version of Guitar Slim's "The Things That I Used To Do" (rendered as a

kind of response to Jimi's "Red House"), it became clear to one and all with

Stevie Ray's near-faithful rendition of "Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)," which

became a concert favorite.

In 1984 Couldn't Stand The Weather was released, along

with a video - Stevie Ray's first - made for the title cut. The typically Texas-macho

clip received moderate airplay on MTV. This wider exposure helped push the album to

platinum and further cemented Stevie Ray's status as the reigning Texas Guitar King. As

he continued to forge his own identity on slightly-behind-the-beat Texas shuffles like

"Cold Shot" and "Honey Bee," he simultaneously pursued the ghost of

Jimi Hendrix, much to the delight of his young fans. If the connection was not apparent

from his version of Guitar Slim's "The Things That I Used To Do" (rendered as a

kind of response to Jimi's "Red House"), it became clear to one and all with

Stevie Ray's near-faithful rendition of "Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)," which

became a concert favorite.